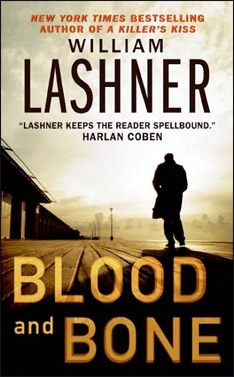

Blood and Bone by William Lashner

Blood and Bone

Excerpt

Kyle Byrne spied his father watching him play in the seventh inning, which was a little disconcerting considering his father had been dead for fourteen years.

It was on the diamond at the Palumbo Recreation Center at 10th and Fitzwater, during a lethargic Monday night beer league-softball battle between Dirty Frank’s and Bubba’s Bar and Grill. The field was scabrous, the fence surrounding the lot was close and high, the bleachers were dotted with family and friends getting a start on the evening imbibitions. Kyle, Bubba’s shortstop, was sitting on the bench, having a few swigs of his own from a can of Rolling Rock as Bubba Jr. looked on disapprovingly.

“What’s the rush?” said Junior. “I need you sober.”

“Dude.”

“Don’t dude me, dude. I been duded enough by you to last me through the rest of the decade. What I need from you is to close my bar tonight.”

“Junior, I’m finding your lack of faith in me frankly dispiriting. I said I’ll be there.”

“You said the same thing last Monday.”

“But you should have seen her. I mean, my God. And she had these little puppy dog eyes.”

“Puppy dog eyes?”

“You know, the ones that are just saying ‘Pet me, pet me.’ How could I resist that?”

Bubba Jr. tried to stare Kyle down.

“‘Pet me,’” said Kyle in his little dog voice.

“You seeing that puppy again?”

“If I can find her number. It’s in some pocket or other, I don’t know.”

“But you do know you’re going to see me again. Think about that next time you’re deciding who to screw.”

Bubba Jr. was about as unBubba-like as anyone could be. The bar was named after his father, who at six-two, two-forty, and with a laugh like a trombone, had been Bubba to his bones. A heart attack at forty-eight passed the bar and the name to his small and wiry son.

“I need to be able to rely on my people,” said Junior, “or I’ll find people I can rely on.”

“Aw Junior, this is sad. You should hear yourself talk, ranting on about your people. Reading all those business books is rotting your mind. When did you start going all CEO on us, dude?”

“In January, when my father died and left me the stinking bar. By nine-thirty, all right.”

“You don’t need me till ten.”

“Nine thirty.”

“It’s under control,” said Kyle, before downing the rest of his beer. “I love you, dude. I do. Not as much as I loved your father, but then he never read a business book in his life. You know I’m there for you, Junior. Stop worrying.”

“Okay, fine, I’ll stop worrying. Now grab a bat. You’re on deck and we need some runs.”

“You think I’ll get my ups?”

Junior looked through the cage at Old Tommy Trapp, gray, grizzled, toothless as a whelp, awkwardly taking his stance at the plate. “Pitch it in, you pussy,” screeched Old Tommy.

“Like my daddy always told me,” said Junior, “miracles happen.”

Kyle stood, grabbed a bright red bat from the behind the backstop and started swirling it one handed about his head as he surveyed the field.

Bubba’s was trailing Dirty Frank’s, which was a crime, really, because Dirty Frank’s was just about the worst team in the league and Bubba’s had the league’s best player, who was Kyle himself. Bubba Sr. had spotted Kyle playing on that same field in a fast pitch league a few years before. Bubba’s needed a shortstop, Kyle needed an occasional bartending gig to supplement his lack of income, a deal was struck. It had worked out great at the start, but Junior had been taking it all a bit too seriously. To Kyle it had started feeling like a job, and really, who the hell needed that, right?

“They put in a new centerfielder,” said Kyle to his pal Skitch, who was leaning against the backstop. “And he’s playing in. Can he go back?”

“Who, Duckie?” said Skitch. “Like a gazelle.” Skitch pushed his squat upper body away from the fence and spit a glob of sunflower seeds onto one of his cleats. “An overweight gazelle, with two bad knees and a hippo on its back.”

Skitch was about Kyle’s age but a foot shorter and built like a fire hydrant. He played catcher because he ran like a fire hydrant, too. But he also pissed like a hydrant from all the Bubba’s beer he drank, which made him a valuable member of the team, at least to Bubba Jr.

“We’re going out to the McGillin’s after,” said Skitch.

“That dump?”

“You coming?”

“I have the bar tonight.”

“When?”

“Ten.”

“Hell, we’ll be passed out by nine, you won’t miss a thing. I got some friends coming in from Atlantic City you should meet. Friends of the female persuasion.”

“Persuasion? That mean they’re not sure?”

“Oh, they’re sure. Let me tell you something, Kyle, they’re too damn sure for me to handle by my lonesome. That’s why I need you on my wing.”

“How many?”

“Three.”

“Who’s handling the third?”

“Old Tommy’s coming.”

Kyle looked at the geezer at the plate, so skinny it was like the bat was swinging him. “Give me something to hit, you pussy-assed fraud,” shouted Old Tommy at the pitcher in a voice as ragged as his cleats.

“Okay,” said Kyle, who was partial to Old Tommy primarily because he never said a kind or thoughtful word. “But I can’t stay long, I need to be at the bar by nine-thirty.”

“I thought you said ten.”

“Junior’s nervous.”

“Worst thing ever happened to him was inheriting that bar.”

A splash of sound signaled that Old Tommy had slapped a ground ball through the second baseman’s legs. Cheers and claps, catcalls. “You dogs suck pig tits,” shouted Old Tommy from first. “My mother plays better than you and she’s been dead four decades now.” Two on, two outs, seventh and final inning, Bubba’s down by three.

“Get on base and I’ll pick up the winning knock,” said Skitch.

“Last thing you knocked was that Sheryl from Folcroft,” said Kyle as he stepped past Stitch and around the backstop, taking his place at the plate.

The outfielders backed up when he entered the cage. The left fielder was playing in Saskatchewan. It would be easy enough to dump a line drive single in front of him, but that would leave them still two runs down, depending on Skitch to win the game, and the one thing Skitch wasn’t was dependable. The right fielder was also playing away, scratching his back on the fence on Fitzwater Road. But the short fielder was playing in and the center fielder had only retreated a few steps. The left fielder was waving him back, but the center fielder was blithely ignoring him.

Sweet.

Kyle kicked his right foot into the dirt, placed his left foot toward the pitcher, stretched his bat high into the air before letting it gently fall into position at his rear shoulder. Here, at the plate, waiting on a pitch, here, in the middle of this moment, was the one safe place left in his life. Everyone had always told him how good he was at this -- from little league and legion ball, through high school, even at that college before his grades took him down -- how he had a future at this, even if there was no one around to tell him how to reach it. And though things hadn’t worked out, and he wasn’t taking his stance in a major league ballpark but instead waiting on a high arc piece of crap in a beer league softball game, he still felt perfectly at home at home plate.

The pitcher’s arm whirled and the ball flew into the sky and Kyle could see its seams spinning, could almost count them as the ball fell toward the outside of the plate, just what he was waiting for. Keeping his hands close to his body he took his step. And he saw the ball shooting out to deep right center field, the angles the fielders took as the ball soared over their heads, saw it all even before he twisted his rear foot and shifted his hips, even before the red bat whipped around and connected, even before the sweet thwump flowed through his body easy and smooth.

Then he was off and running, towards first base, not sprinting hard, he didn’t need to be, just chugging chugging away, watching the centerfielder back up and spin awkwardly and trip over himself as he scrambled for the ball. The right fielder charged over, but the angles weren’t right. The ball skidded past him off the dirt and toward the fence. Kyle was following it all, the ball, the fielders, the angles that showed the ball rolling free and out of reach as he made the turn at first.

That was when he saw him.

A bob of gray hair, yes that, for sure. And a dark suit, a quick step, a knowing wink in the crouch of the posture. Maybe Kyle imagined the rest, but it all added up to only one thing.

Hello, boyo.

For years after his father’s death, there was a part of Kyle that couldn’t accept the truth of it. Even though he and his father had never been close, and even though he still had a small cardboard box filled with his father’s ashes stashed in the glove compartment of his car, he long treasured the hidden hope that they would still have a tearful reunion. As a boy, whenever in crowds or walking down the streets of the city, he found himself searching for his father. And on the ball fields of his youth, he caught himself checking the stands as involuntarily as a tic, to see if maybe, just maybe, Dad had come to watch him play. Part of Kyle secretly believed that his father had run away, was hiding for some good reason, was waiting for the right moment to come back into Kyle’s life. How many times had his heart leapt at the sight of a shock of white hair, how many times had the vision sent him running, only to see that the man was not his father at all, just some old guy shuffling along?

It had lay dormant for a while now, this secret and forlorn hope, he hadn’t had a sighting in years. But suddenly, here, on this pathetic little field, as he rounded first and headed for second and tracked the ball on its path deep into right center field, beyond the fence on Fitzwater Road he spied the bob of gray hair and just that fast, something broke free in his heart.

He stopped in his tracks. And stared at the gray-headed figure. And the question came out in a breathless gasp, as desperate as the ache that suddenly ripped through his body.

“Daddy?”